Summit County Naturalist Information

Your Donation to FDRD will make a difference!

NATURALIST: AN EXPERT OF NATURAL HISTORY

The Dillon Ranger District, in the White River National Forest is encompassed by many abundant habitats, sustaining the populations of our local flora and fauna. Learn about the wildlife that calls Summit County home, the wildflowers that paint the hillsides during the summer months, the trees that make up our bountiful forests, and the eco-systems and habitats that you will find here in the beautiful Dillon Ranger District.

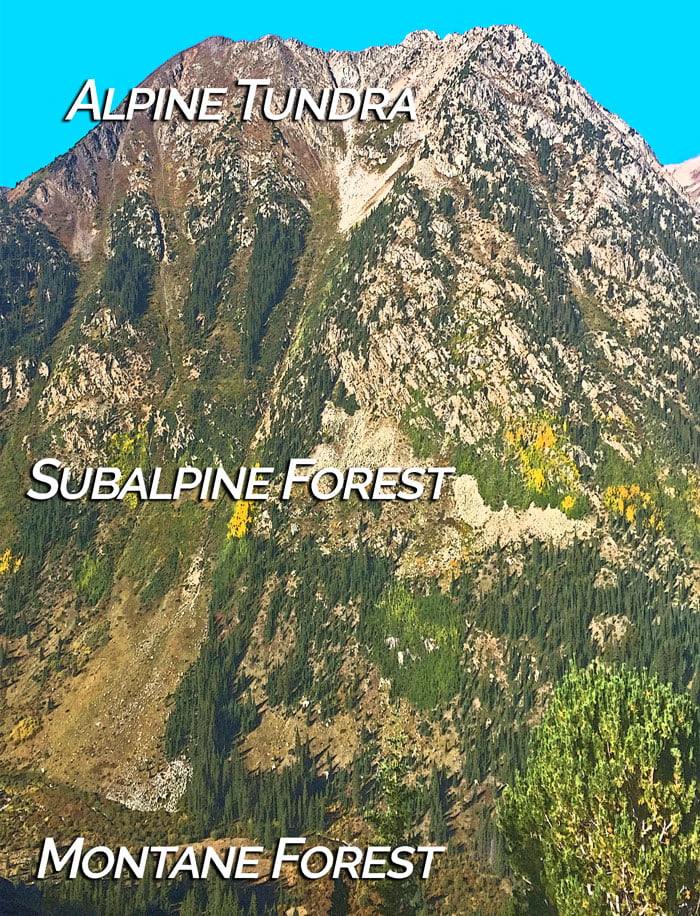

Life Zones of the Dillon Ranger District

8,000 – 10,000 feet

Montane forest at Lower Cataract Lake

- Montane zones consist of bountiful open forest groves of mixed conifers and aspen, sagebrush and wildflower filled meadows.

- Abundant wildlife: Moose, black bear, bobcat, coyote, fox, porcupine, snowshoe hare, and more live in this zone year-round, while deer and elk spend winters here.

- High-altitude riparian zones are plentiful in the montane forest, occuring along rivers and streams of the Dillon Ranger District. According to CSU’s Colorado State Forest Service, montane riparian forests make up roughly 1 million acres in Colorado and account for 4 percent of the state’s forested lands. Learn more about the importance of riparian zones from local environmentalist, Sustainable Hiker.

10,000 – 11,500 feet

Subalpine forest in the Eagles Nest Wilderness

- Due to more precipitation and streams and springs fueled by snow runoff, meadows are covered with a large variety of wildflowers and many conifers including spruce, firs and pines. Bristlecone pine can be spotted on rocky slopes along with patches of blue and Engelmann spruces.

- Elk and deer migrate to this zone in the summers to find plentiful food. Canada lynx, bighorn sheep, moose, mountain lions, and marmot could also call the subalpine forest home.

Above 11,500 feet

Alpine Tundra on Teller Mountain in Montezuma

- This zone extends from the treeline to the highest altitudes and mountain peaks.

- The tundra is a fragile, treeless area with low-growing grasses, shrubs, and wildflowers that have adapted to the severe environment and very short summers.

- Yellow-bellied marmots and pika dwell in the rocky, talus slopes and mountain goats traverse the steep jagged cliffs.

Wildlife

Moose

Name means “twig eater” in the Algonquin language. Found in wetland willows and the forest. They can be aggressive if threatened.

Elk

In winter found in mountain valleys; in summer near timberline. Fall mating call is a distinctive “bugle.” Listen to Elk Bugle

Mule Deer

Gray in color, known for large “mule size” ears. In winter found in mountain valleys and in summer, forest wide.

Mountain Goat

White with black horns. Found above timberline on steep, rocky slopes. Male is bigger with larger horns. Often unafraid of humans.

Bighorn Sheep

Tan colored. Male has large curved horns; female has smaller spikes. Found on rocky, exposed cliffs and talus slopes.

Black Bear

All Colorado bears are “Black Bears,” yet colors range from black and brown to cinnamon. Take precautions with food/ garbage in bear country.

Mountain Lion

Large cat often found where deer and elk are abundant (main food source.) Usually solitary animals; very secretive.

Canada Lynx

Cat with grayish brown fur, ear tufts; longer back legs and large snowshoe-like paws. Protected as a “Threatened Species.”

Bobcat

Cat with gray to brown spotted coat and black-tufted ears. Can be mistaken for lynx, but have shorter legs and smaller paws.

Coyote

Medium-sized canine; gray to tan with a bushy tail. Makes a variety of high-pitched howls, yips, yelps, & barks. Listen to coyote howls

Red Fox

Small canine, usually reddish in color, some can be grey/black. Has long, bushy tail with white tip. Unafraid of humans.

Porcupine

Nocturnal, loves to chew. Eats tree bark and plants. Cannot throw quills, but each is needle sharp and barbed. Forest dweller.

Snowshoe Hare

Forest dweller. Changes color with the season: brown in summer, white in winter. Can run up to 32 mph.

Yellow-Bellied Marmot

Large rodent found in open, high-alpine habitats. When approached, marmots give a warning whistle – hence their nickname, “whistle pig.”

Pika

Small relative of the rabbit, lives in talus slopes at or above timberline. Gathers flowers and grasses all summer for its winter food supply.

Beaver

Large rodent found in wetland areas building dams, canals, & lodges. When alarmed, dives rapidly while slapping its tail on water.

Wildlife photos courtesy of Ruth Carroll & Elaine Collins

Raptors

Bald Eagle

National emblem of the United States. Usually found near large bodies of water.

Golden Eagle

Eats a variety of prey – mainly hares, rabbits, marmots, and ground squirrels.

Osprey

Nests near any body of water, almost exclusively eats fish.

Red-Tailed Hawk

Highly variable diet, mostly small mammals and rodents – prefers terrestrial, diurnal prey.

Peregrine Falcon

Known for speed, can reach up to 200mph when diving. Eats primarily medium-sized birds.

Great Horned Owl

Primarily eats hares, rabbits, rats, mice, and voles. Excellent camouflage makes it hard to spot.

Birds

Raptor & bird photos courtesy of Ruth Carroll

- Black Bears are very food driven in the summer and fall in order to load up on calories for their winter hibernation – they will explore all possible food sources. They will search near homes, campsites, and communities. If they find food, they will come back for more.

- When camping, all food and cookware must be stored in either a locked vehicle, a designated bear proof container, or hung from a tree branch (at least 6 ft. off the ground and 6 ft. from the tree trunk)

- If you see a bear looking for food, bang pots and pans and yell and scream to associate loud, unwelcoming noises with this food source.

- NEVER corner a bear, this could cause it to become aggressive.

- If you see a bear on the trail, make noise and make yourself look big by waiving your arms above your head. Back away from the bear while doing this off the downhill side of the trail.

- Learn more from Colorado Parks and Wildlife

- Moose are the most dangerous animal in Colorado, and they are not afraid of humans.

- Although they are beautiful and can often seem clumsy and aloof, they are capable of reaching speed of 35 mph and can charge when they feel threatened.

- Moose react to dogs as they would to their natural predator, wolves.

- They will defend themselves and their young very aggressively, especially when barked at or chased.

- How to avoid a dangerous confrontation with a moose:

- NEVER approach or try to feed moose.

- Give moose plenty of space if you see them.

- Moose hang out in wetland areas, be aware of moose when hiking in wetlands.

- Moose are protective of their babies, so if you see a baby moose, leave the area immediately.

- Keep your dog on a leash.

- In the presence of a wild animal, even the most well-behaved dogs quickly revert to primitive instincts and will chase, bark, or attack.

- Domestic dogs lack the hunting skills of their ancestors, and often end up injuring wild animals.

- Dogs off leash can chase a mother animal away from their young, and the abandoned baby animal often dies.

- A dog off-leash is easy prey for wild predators like mountain lions or coyotes.

- All dogs must be leashed at all times, (no longer than 6 ft.) in any designated Wilderness Areas.

- Leaving your trash, food, and waste behind is illegal and degrades wildlife habitat and water sources.

- Human food that is left unsecured can habituate wild animals, like foxes and black bears, to seek human food sources and ultimately lead to the animal’s death.

- FEEDING OR BAITING WILDLIFE (NO MATTER HOW BIG OR SMALL) IS ILLEGAL!!

- Our favorite places to recreate are also home to deer, elk, moose, black bears, mountain lions, mountain goats, foxes, coyotes, porcupines & more.

- Wild animals are most active at dawn and dusk and night, and may be taking a nap somewhere near your favorite path during the day.

- Approaching any wild animal is not only dangerous and unethical, but can result in legal charges of harassment of wildlife.

- Certain areas are closed to human activity during winter and spring to protect wildlife.

- Mountain bikes, dirt bikes, and ATVs that illegally go off-trail, erode the landscape and damage vegetation that wild animals rely on for forage and shelter.

- Wildlife will flee when frightened by fast movement and noise, (hikers, bikers, snowmobiles, dogs) using up their critical energy reserves.

- Disturbance can lead to starvation, and in the springtime can also lead to abandonment and death of newborns.

Please remember to stay on the trail, leash your dog, keep your distance, and do not litter or feed. Colorado Parks & Wildlife encourages you to watch and enjoy YOUR wildlife, but do it responsibly, and from a distance!

Trees

Blue Spruce (Picea pungens)

Colorado’s state tree. Has sharp, blue-green colored needles and grayish-brown scaly, rough bark. Cones are 2-4″ long.

Engelmann Spruce (Picea engelmannii)

Also called white spruce, mountain spruce, or silver spruce. Has sharp needles and grayish-brown, scaly, rough bark. Cones are 1-2″ long.

Subalpine Fir (Abies lasiocarpa)

Needles are soft and flat. Cones are black/purple and long. Firs have a silvery smooth bark when they are small.

Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta)

Needles grow in twisted clusters of two. Cones are closed and must be exposed to extreme temperatures (i.e. wildfire,) in order to open and spread seeds. Most here have been affected by pine beetles. Red needles indicate dead or dying trees.

Colorado Bristlecone Pine (Pinus aristata)

Long-living Bristlecone pine tree species usually found at very high altitudes (7,000-13,000 ft.) Bark is grey-brown, thick & scaly, needles grow in bunches of five, cones are longer than the lodgepole pine.

Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides)

Deciduous trees with heart shaped leaves and silvery/white bark. Aspen groves are one large organism connected at the root system. Leaves turn bright yellow in the fall.

The Mountain Pine Beetle

The recent Mountain Pine Beetle epidemic, responsible for killing millions of lodgepole and ponderosa pine trees from New Mexico to Alaska, is now in decline. In the wake of the Mountain Pine Beetle outbreak, we can play a role by encouraging the diversity in tree species and ages necessary for overall forest health by actively managing our public and private lands. Some forests may grow back with more natural diversity than exists today, and others may regenerate back to single-aged lodgepole pines.

Visitors to our area will likely notice sections of the forest in which dead trees have been removed. These range from corridors cleared alongside trails, roads, and power lines, to multiple acres of clear cuts near our communities. These areas have been treated to reduce the risks posed to humans, our infrastructure, and our water supply by removing trees and buildup of native fuels. These areas are monitored for regeneration and replanted if necessary. As the young forest continues to develop, the U.S. Forest Service and other public land managers can actively encourage diversity away from a single species of pine trees. In other cases it will monitor, gather information, and practice adaptive management to avoid the situation seen today.

Wildflowers

Alpine Sunflower

(Phymenoxys grandiflora) Sunflower Family | Life Zone: Alpine

American Bistort

(Bistorta bistortoides) Buckwheat Family | Life Zone: Subalpine – Alpine

Arrowleaf Balsamroot

(Balsamorhiza sagittata) Sunflower Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Montane

Blue Flax

(Linum lewisii) Flax Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Subalpine

Colorado Columbine

(Aquiligia coerulea) Buttercup Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Alpine

Red Columbine

(Aquilegia elegantula) Buttercup Family | Life Zone: Montane – Subalpine

Elephant Heads

(Pedicularis groenlandica) Figwort Family | Life Zone: Montane – Alpine

Green Gentian

(Frasera speciosa) Gentian Family | Life Zone: Montane – Alpine

Kings Crown

(Rhodiola integrifolia) Stonecrop Family | Life Zone: Subalpine – Alpine

Subalpine Larkspur

(Delphinium barbeyi) Buttercup Family | Life Zone: Subalpine

Silvery Lupine

(Lupinus argenteus) Pea Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Subalpine

Mariposa Lily

(Calochortus gunnisonii) Lily Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Montane

Moss Campion

(Silene acaulis) Pink Family | Life Zone: Alpine

Parry's Gentian

(Gentiana parryi) Gentian Family | Life Zone: Montane – Subalpine

Parry's Primrose

(Primula parryi) Primrose Family | Life Zone: Montane – Alpine

Pasqueflower

(Pulsatilla patens) Buttercup Family | Life Zone: Montane – Subalpine

Prairie Smoke

(Geum triflorum) Rose Family | Life Zone: Montane – Subalpine

Purple Fringe

(Phacelia sericea) Waterleaf Family | Life Zone: Subalpine – Alpine

Queens Crown

(Rhodiola rhodantha) Stonecrop Family | Life Zone: Subalpine – Alpine

Rocky Mtn. Penstemon

(Penstemon strictus) Figwort Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Montane

Rosy Paintbrush

(Castilleja rhexiifolia) Figwort Family | Life Zone: Subalpine – Alpine

Scarlet Gilia

(Ipomopsis aggregata) Phlox Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Montane

Showy Daisy

(Erigeron speciosus) Sunflower Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Subalpine

Sky Pilot

(Polemonium viscosum) Phlox Family | Life Zone: Alpine

Sugar Bowl

(Clematis hirsutissima) Buttercup Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Montane

Sulphur Paintbrush

(Castilleja septentrionalis) Figwort Family | Life Zone: Montane – Subalpine

Tall Chiming Bells

(Mertensia ciliata) Borage Family | Life Zone: Montane – Alpine

Western Monkshood

(Aconitum columbianum) Buttercup Family | Life Zone: Montane – Subalpine

White Geranium

(Geranium richardsonii) Geranium Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Subalpine

Wild Iris

(Iris missouriensis) Iris Family | Life Zone: Foothills – Subalpine

Invasive Weeds

Medium sized flower heads with bulging yellow centers and fine feathery leaves. Annual plant with seeds that reproduce prolifically and choke out native wildflowers.

Removal: pull plants from the base of the stem, which come up easily. Bag and destroy plants, especially seed heads.

Highly invasive and hard to remove. Usually red/pink flowers and very prickly leaves and stems.

Highly invasive and hard to remove. Usually red/pink flowers and very prickly leaves and stems.

Biennials: Second year Musk Thistle plant bolts and at the stalk end will be a large, red bloom, first year plant is a flat rosette only. Other biennials are bull and plume, both with red heads.

Removal: Do not pull mature plants out of the ground as it will only encourage root spread. Use a commercial weed killer sprayed at the base of the plant. Cut off the flower head and bag so that the seeds do not spread. Small plants may be pulled and destroyed.

Colorado has a native thistle that is hard to distinguish from invasive varieties. It is better to have a native thistle be lost as collateral damage than to have an invasive thistle spread.

Tall biennial plant that can grow to 10 feet with small yellow flowers and soft fuzzy leaves. One plant can have up to 100,000 seeds that can last up to 100 years.

Removal: Dig up plant or use commercial weed killer

Also known as “camper’s friend” for the soft leaves

This should not be confused with the native Green Gentian Monument Plant that is also extremely tall with whitish four petal flowers and long narrow leaves.

Two tone yellow flowers with double lips in a dense column and a trailing spur. Narrow gray green leaves.

Removal: pull and destroy. May take repeated efforts to eradicate.

This wild snapdragon is a troublesome and aggressive weed.

History: Yellow Gold to White Gold

By: Rick Hague

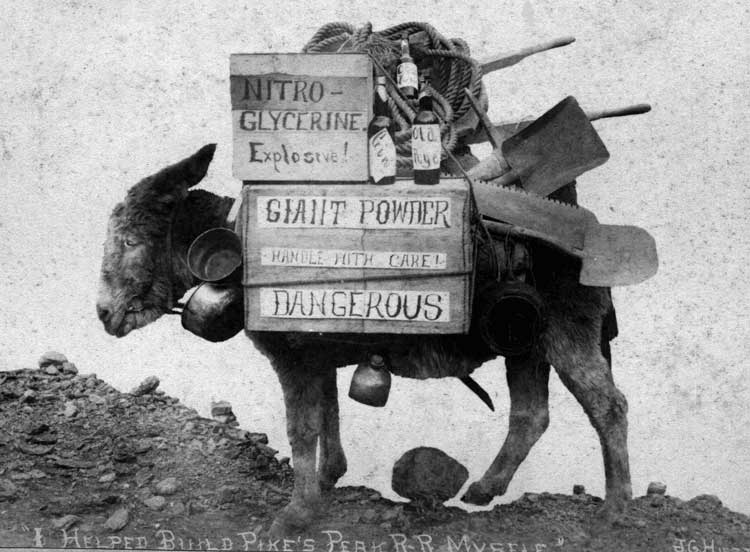

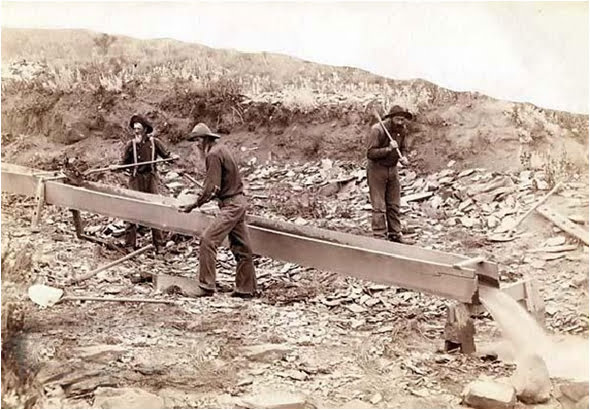

For over 100 years, these mountains heard the drilling, blasting, and shoveling of miners searching for gold and silver. In recent years, these sounds have been replaced by the “swish” of ski against snow and the loud sounds of snowmobile enthusiasts roaring through the forests. The most recent history of Summit County is all about the era of “white gold.”

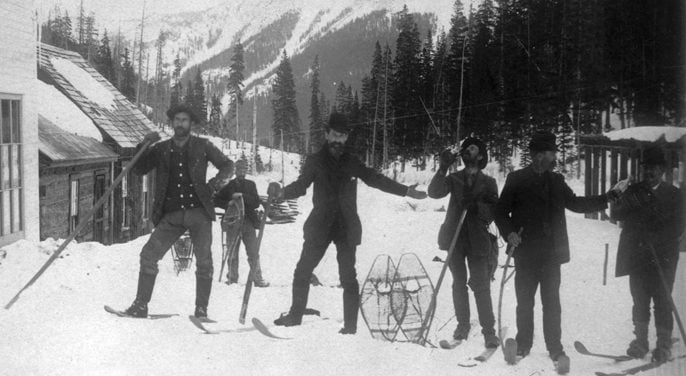

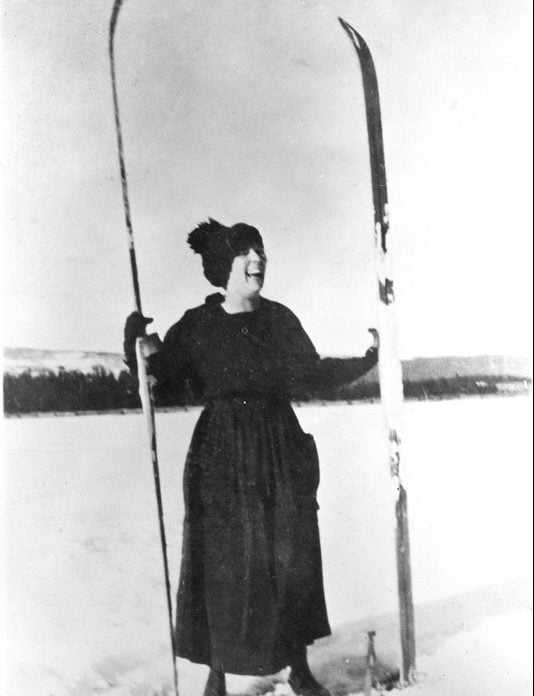

While the beginnings of modern skiing can be traced to Summit’s early days, skiing was almost entirely for transportation during the Pikes Peak gold rush in the 1860s. The equipment differed significantly from that seen on today’s ski slopes. In fact, early skis, which were actually called snowshoes, were made of wood and measured 10 to 12 feet in length. The skier steered and stopped with a single wood pole dragged behind him. Local preacher Father Dyer probably best exemplified this type of ski transportation. He skied between early gold mining camps during the winter to deliver mail and to preach sermons.

Photographs and accounts of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries indicate that similar equipment was used not only for transportation but for recreation and perhaps even competition. It appears that much of the early recreational skiing resembled today’s cross-country or Nordic skiing.

In 1910, a Norwegian named Peter Prestrud, who lived in Frisco, introduced what became a popular local sport – ski jumping. It became so popular that just after WWI, residents constructed ski jumps near old Dillon, Breckenridge, and elsewhere. In 1919, Anders Haugen, a famous Norwegian skier, jumped to a world record of 213 feet at the Dillon jump located near the present-day Glory Hole/overflow outlet of the Dillon Dam. The following year he broke his own record with a jump of 214 feet.

In the years leading up to the 1960s, Summit County saw a great deal of recreational skiing in which women wearing long dresses and men enjoyed outings using long wooden skis. A number of privately owned ski areas opened to the public for downhill skiing in this period as well. In the mid-1930s, the Hoosier Pass ski area opened and probably hosted skiers until the early 1940s. Two parallel cleared runs can still be seen to the left of Route 9 when ascending Hoosier Pass. One of the original four log cabins still stands within view of the old runs.

Chalk Mountain, located at the top of Fremont Pass, between Copper Mountain and Leadville, and directly across the road from the present-day Climax Mine, opened in 1934- 35. Built by Climax Mine employees and used mainly by them, the area also welcomed the public before closing around 1962.

Arapahoe Basin Ski Area, located on Route 6 below and just west of Loveland Pass, was developed by 10th Mountain Division veterans and locally famous, Max and Edna Dercum. It opened to the public in 1946 and is, of course, alive and well today and very much a part of modern-day Summit County skiing.

But the real story of modern skiing in the county began in about 1959 when Wichita, Kansas-based Rounds and Porter Lumber Company (RPLC) became interested in acquiring land in Summit County to build a year-round, second-home recreational community. RPLC was not only a purveyor of lumber products but also a real estate developer and oil and gas explorer. The Dillon Reservoir, under development at the time, and the magnificent snow-covered mountains surrounding Breckenridge attracted the company for their winter and summer recreation potential.

Exploration geologist Bill Stark was an acquaintance of RPLC executive Bill Rounds, and a skiing enthusiast. Stark approached Rounds with the thought that the mountains around Breckenridge offered the potential for winter activities to compliment the summer, water-based recreation activities at Lake Dillon. Rounds, when skiing in Aspen in 1959-60, recruited the services of two Norwegian ski instructors to help evaluate the potential of Breckenridge. And, as the saying goes, the rest is history.

In 1960, the company submitted an application to the U.S. Forest Service for a permit to build a ski area on Peaks 8, 9, and 10. The Forest Service completed its evaluation in March 1961, and granted a permit on July 27, 1961, for 1,764 acres. Trail cutting on Peak 8 began immediately. The “Peak 8 Ski Area,” its original name, opened for business on December 16, 1961. Depending upon who you ask and what you consider a “run,” either six or seven original runs (Springmeier, Rounders, Swinger, Crescendo, Four O’Clock, Boreas Bounce, and Ego Lane) awaited skiers at the new area.

Over the years, crews cut many more trails and built more lifts on Peak 8. Peaks 9, 10, 7, and 6 opened in subsequent years in that order. The Bergenhof Restaurant on Peak 8 served its first customers during the 1961-1962 season, while the Vista Haus began operating during the 1997-1998 season on Peak 8. Peak 9, originally named Royal Tiger Mountain, opened in 1971- 1972 with a restaurant, originally named the Eagle’s Roost and subsequently re-named the Peak 9 Restaurant and The Overlook, first providing meals during the 1973-1974 season.

Peak 10 came next, during the 1985-1986 season, with the TenMile Station restaurant welcoming diners in 1998-1999. Peak 7 followed in the 2002-2003 season and then Peak 6 in 2013-2014, rounding out what today is the Breckenridge Ski Resort. Other notable dates at Breckenridge include the inauguration of the Peak 8 SuperConnect, connecting Peaks 9 and 8, during the 2002-2003 season, and the construction of the BreckConnect Gondola for the 2006-2007 season.

Elsewhere in the county, Keystone Ski Resort opened in 1970-71, while Copper Mountain opened the following ski season.